News of Missionary’s Death Underplayed Amid Vigilance in Ecuadorian Village

To a few people in Tiwino and several other villages in Ecuador’s Amazon region, Monday June 15, may have been significant in that thousands of miles away in the U.S., Elisabeth Elliot died at age 88.After a successful career as a Christian author, radio program host and conference speaker, Elliot passed “through gates of splendor” for her eternal heavenly reward, according to Christian media reports that artfully reprised the title of her first book, Through Gates of Splendor. A memorial service is set for Sunday, July 26, in Edman Chapel at Wheaton College in Wheaton, Ill.

In the book published in 1957, Elliot recounted how just a year earlier five missionaries—one of them her husband—died in their efforts to spread the gospel to a violent tribe in Ecuador that lived a Stone Age existence. Once known as Aucas, they are more accurately known today as Waorani (plural) or as Wao (singular) which is pronounced like the exclamative, “wow.”

These days, descendants of those Waorani live a different lifestyle, having set aside revenge for the most part. They use their spears for hunting. Features such as forgiveness and reconciliation have propagated the culture of those who follow the teachings of Christianity.

To some of the Waorani—if they’ve received word of the death of Elliot, a former missionary to Ecuador—the news may have been overshadowed by another event. That event has been termed a potential threat to one of the small communities some distance from the place where the five missionaries died on the Curaray River in the Ecuadorian rain forest. Less than a week before Elliot’s death in Magnolia, Mass., Tiwino was placed on alert. Witnesses had reported seeing nearby some people whom they believed were part of a reclusive group known as Taromenane.

Even as many Waorani have found ways to co-exist or even assimilate into an encroaching dominant culture, the Taromenane, biologically related to the Waorani, have withdrawn into the jungle. The Tarome—with a different spelling in the Wao* language—signifies that they are over landers whereas other subset groups are known as either upriver or downriver people. Their contacts with the other Waorani have been sporadic and at times lethal as traditional revenge killings at times have returned.

“On June 5 the Waorani spotted some 200 meters away people who are possibly Taromenane,” reported the Quito newspaper, La Hora. Another Quito daily, El Telégrafo, stated that “the Ministry of Justice, Human Rights and Religious Affairs, through the Directorate for the Protection of Indigenous Peoples in Voluntary Isolation, activated the Protection Protocol that allows monitoring and tracking.”

A multidisciplinary team of physicians, local Waorani and government workers are in Tiwino to help with contingencies in case hostilities develop between the two indigenous groups.

Contact by Outsiders Leads to Cultural Changes

The older Waorani—as well as some Amazon-region Quichua and the Tsachila people of Ecuador’s western jungle—remember that Elliot and other evangelical Christians contributed to cultural changes. Some recall the Waorani abandoning a lifestyle of killing in the 1950s and 1960s and embracing the gospel of Jesus Christ.

For centuries before the gospel was preached in Ecuador’s Amazon region, violence had awaited those who trekked in. People did not return if they went into Waorani territories. The Waorani, in addition to killing outsiders, also turned their long spears of sharpened chonta palm wood onto each other in revenge killings.

Few Waorani lived to an old age, for spearing deaths were common. The naked forbears of today’s Waorani roamed a vast area of the jungle and were known by the term “savage” (or Auca) by Ecuador’s lowland Quichua people with whom Elliot was acquainted.

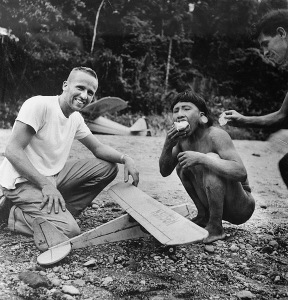

“We were working with the jungle Quichua tribe and reducing their language to writing, doing some Bible translation,” recalled Elliot in a mid-1990s interview with Reach Beyond’s Curt Cole that aired on Radio Station HCJB. (Then a program host, Cole now serves as the mission’s senior vice president of international ministries.) Elliot related that Mission Aviation Fellowship (MAF) pilot Nate Saint “came in one day with a very exciting piece of news, which was that he had discovered the whereabouts of a tribe that no one had been able to contact.”

In the home of Nate and Marj Saint in Shell, Ecuador, the missionaries anticipated reaching out to the Waorani. Elliot told Cole that her husband, Jim, and others “made the attempt to go in after a very long and careful planning period and dropping of gifts to these people with the hope that they might reduce the hostility.”

“When they received what appeared to be very positive signs of friendliness,” she said, “they felt that it was time to move into the edge of their territory and set up camp. They did not go barging into the Auca houses. But they hoped that the Indians would find them. They prayed that this would happen … and it happened.”

Evangelistic Efforts Defy All Odds

The Waorani found the five missionaries at the river and befriended them. Elliot told Cole that “two women and one man had come out and exhibited such friendliness that they actually ate the stuff the men gave them, can you imagine—a hamburger with mustard and lemonade—things that were not remotely like anything they’d ever seen.”

However, their evangelistic success seemed short-lived as other Waorani came and killed all five of them, leaving the plane shredded but largely intact on the shore of the Curaray River on Jan. 8, 1956. Marj Saint had waited for a Sunday-afternoon call on the radio from the men. But no call came. Days afterwards in the Saints’ kitchen, Dr. Arthur Johnston, a missionary physician serving at Hospital Vozandes-Shell, helped to inform Elliot and the other wives that their husbands had all been killed.

Elisabeth

Elliot (second from right, holding Valerie) with the other four

missionary widows. Left to right: Marilou McCully, Barbara Youderian,

Olive Fleming, Elisabeth Elliot, Marj Saint.

“As we contemplate that God has given victory and that there is wonderful evidence of His sustaining grace,” Jones continued, “we would like to urge all of you to pray clearly and definitely for further consolation from the Lord for these five women who definitely need the guidance, instruction and help of the Lord in these very trying days.”

In regular contact with NBC, Jones told the New York City-based radio and television network that findings by the search committee that went to the Curaray indicated, “that there was a sudden attack of some kind, and evidently they were dealing on a friendly basis with the Auca Indians and were taken by such sudden surprise that five strong men were immediately killed.”

Tale of Two Villages: Tiweno and Tiwino

Two years later (in 1958) Elliot went to live among the Waorani with her young daughter, Valerie, and Rachel Saint, whose brother, Nate, had also been killed by spearing. Together they ministered to the Waorani for about two years, and those who killed the missionary men were some of their first converts. After that, Elliot moved to the U.S. with her daughter.

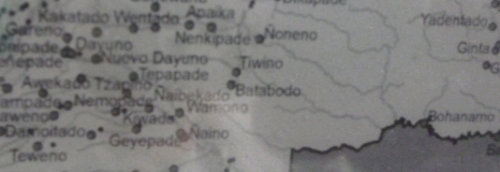

Tiwino [Tigüino], site of the present alert in Ecuador’s Amazon region, is not the same community as Tiweno [Tihueno], a settlement sewn with the seeds of Christianity in Rachel Saint’s earlier years in Ecuador.

At one point in the late 1960s however, Tiweno attracted warring factions of Waorani, with Saint in the middle of it all. Reach Beyond retired physician Dr. Wally Swanson related decades afterwards that, “here was a group from the south [jungle] and a group from the north [jungle] meeting at Tiweno with a group that had been only their enemies in the past—that they had fought with and killed and speared.” Swanson researched and documented the Waorani as part of his medical licensing in Ecuador.

Swanson interviewed Waorani for the research, learning that “there was not one single male adult in their living memory—grandfathers, great grandfathers, uncles—that had … not died by spearing.”

“All of them had died violently,” Swanson continued. “And 75 percent of the women and children who had died (whom the interviewees knew about and could remember) had died in the same way.”

“The tendency to idealize or romanticize ‘primitive’ cultures falls to crushing blows … as the reality of life in the upper Amazon rainforest plays out in gruesome details often too explicit and vivid for the cushioned Western mind,” wrote Jim Yost and Chet Williams in the foreword of a book in which three Waorani tell of life before and after encountering Jesus Christ.

Analyzing the Waoranis’ traumatized collective psyche, Yost continued that “in the first decade that I lived among the Waorani, I doubt a day ever passed that I didn’t hear the wrenching stories of past atrocities.”

Kawia

(with open Bible) sits between Menkaye, on his left and another person.

Kawia and Menkaye are literate and both are Christians. Photo by Daniel

Klassen.

The book itself, published in 2013, was authored by the missionaries’ killers at the beach, Menkaye Ænkædi (with friends Kemo and Dyowe). If it strips away support of the noble savage literary concept, so too does the book address evangelical renditions of the Waorani story. Most are told exclusively from a Western context. Additionally, a literature review might leave researchers and others with the idea of mission accomplished.

Truly, the culture has changed; that is undeniable. Menkaye, however, insisted upon the title, Gentle Savage Still Seeking the End of the Spear, according to translator Tim Paulson, “because it’s been stated in the outside world that the days of spearing among the Waorani are over, which is far from the truth. It’s still very much a way of life, especially for the Tagaeri and the Taromenane who remain isolated and intentionally out of reach by even the upriver Waorani. But even among the upriver Waorani, who have had significant contact with the outside world, spearing is far from over.”

Circumstances amid tribal tensions in Tiweno in the late 1960s worsened when a polio outbreak began to take people’s lives and mutual suspicions grew on just whose sorcery was behind it. But Swanson and other missionaries were called in by Rachel Saint.

They capably rescued those they could with evidence-based medical diagnoses and by using rudimentary equipment similar to playground seesaws to keep the polio victims breathing. Not all the Waorani lives were saved, Swanson said, and missionaries successfully convinced the survivors that the bodies of those who had died were not cannibalized by the foreigners.

After more than 35 years among the Waorani, Saint died and was buried at the village of Toñampare near the site where her brother and the four other men were killed on the Curaray River. The village is named after a stream that runs through the area. Toña, a Waorani born there, later became an evangelist and was killed in his attempt to share the gospel of Christ with a hostile subgroup, according to Ethel Wallis in her book, Aucas Downriver.

Oil Exploration Encroaches on Indigenous Groups

Because life always moves on, the Waorani story does not freeze frame where Elliot’s book ends. So too, development in the Amazon region threatens the hunter/gatherer lifestyle of the Taromenane as oil exploration and extraction continues. When in March 2013 in Ecuador’s Orellana province, two elderly Waorani, Ompore Omeway and Buganey Caiga, were speared to death, the suspicions of fellow Waorani fell on the Taromenane. The spearings occurred near the village of Yarentaro at the edge of the Yasuní Preserve where the Taromenane still roam freely.

Rumors abounded and different antecedents were offered as possibly explaining the motivations behind the killings. One generally accepted theory centers around deaths of the Taromenane from contaminated food dropped from an aircraft. Another explanation was that the Taromenane viewed Omeway as a liaison between their world and that of the cowode (outsiders). When his advocacy failed, the relationship went awry.

A year after the elderly Waorani were killed, approximately six Waorani men were imprisoned for what court proceedings determined were their roles in avenging the couple’s deaths by killing up to 30 people.

The “official version” of what happened, according to a statement by the Organización de la Nacionalidad Waorani de Orellana (Waorani Nation Organization of Orellana or ONWO) was based upon conversations with families and relatives of Omeway and Caiga. The statement also lamented about the loss of land to “deforestation, agriculture and cattle ranching.”

The ONWO account stated that the Taromenane had “expressed their anger to Omeway and Caiga about the noise, unknown crop planting, too many cowode [outsiders], trees being cut down and [oil rigs].” The Taromenane had demanded advocacy by the Waorani couple with the outsiders, but “evidently, Omeway and Caiga could not help,” indicating this may have provoked the attack.

When a judge dismissed the case against them, the prosecutor, Andrew Causapaz, submitted a motion for “nullification and appeal” of the dismissal. Causapaz said in an appeal hearing that the allegations against the Waorani were based in part on pictures they had taken, along with shotgun shells, pots with traces of pellet impacts and up to 100 other pieces of evidence. Initially, the Waorani were charged with genocide, but the charge was amended to murder in compliance with a provision of the Constitutional Court that also studied the case.

Ecuadorian Attorney General Galo Chiriboga had indicated in mid-2013 that Ecuador’s government would exact justice for the deaths and not repeat the error of 2003, referring to internecine violence by Waorani fighters against the Taromenane.

No formal charges followed the 2003 killings. An international body, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, later requested Ecuador’s protection for the nation’s non-contacted peoples, and government officials granted the request. Ecuador’s protection protocol, implemented by the Directorate for the Protection of Indigenous Peoples in Voluntary Isolation, is Ecuador’s answer to that request from more than a dozen years earlier.

Given the complexity of the situation, can forgiveness or reconciliation prevail? Will the impact of the gospel message—one that Elliot promoted in her early years in Ecuador and that Waorani believers live by today—someday, somehow reach the unreached Taromenane?

*Waorani can also be spelled Taadömënäni (taadö for trail and näni which is plural). So too, Waorani is used by outsiders whereas Waodäni more accurately reflects the linguistic realities of the Wao language.

No comments:

Post a Comment